‘It’s a small step to a massive change for these children. Everything that we do is in collaboration, we are working together for these children, so that everything matters. We’ve got to get it right. They’re not going to stop now. Kenton says that he's working on a character now about everything that’s been taken from our world. So he's gonna create this character to give life back.’

In June 2023, this exhibition of digital artworks by younger people from the town of Ieramagadu (Roebourne) on Ngarluma country opened at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra on Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country. It ran until 2 October 2023.

The digital artworks were created in NEO-Learning workshops at the Digital Lab, a creative space on the main street of town. The Digital Lab was established by Big hART and the Ieramagadu/Roebourne community as part of the New Roebourne Project (a legacy of the Yijala Yala project).

Below is a collaborative evaluation of GULGAWARNIGU. Thinking of something, someone is compiled by Associate Professor Sarah Holcombe (University of Queensland, Australia) and Professor Kerrie Schaefer (University of Exeter, UK) with the support and assistance of Big hART CEO and Artistic Director, Dr Scott Rankin, and Partnerships Manager, Lucy Harrison. Co-authors are Patrick Churnside, and Samantha, Isaac and Kenton Guinness.

The immersive tour was facilitated by Big hART creative producers, Mark Leahy and Bodhi Aulich-Croll. Our sincere thanks to this Roebourne-based Canberra-touring team for their facilitation and assistance, in sharing materials with us that are included below.

This project was funded by the QUEX Institute, an initiative of the Universities of Queensland, Australia, and Exeter, UK.

Header Image: Michelle Adams, Samantha Walker with sons Isaac and Kenton Guiness, Patrick Churnside, Bodhi Aulich-Croll, Mark Leahy (L to R). Sat Jun 3rd 2020, photographer unknown (gallery visitor/passerby).

TOURING THE EXHIBITION: Wayiba! Wanthiwa! Hello! Entering Ieramagadu (Roebourne) in Canberra

This exhibition of digital artworks is introduced by two younger artists, Isaac Guiness (early high school) and Kenton Guinness (primary school). These two represent at least 20 younger digital artists from Roebourne who’ve been involved in creating artworks over several years (including during the pandemic) based at the Digital Lab created by Big hART and sustained by Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi communities in Roebourne. Isaac and Kenton have been at the gallery speaking at the public opening of the exhibition and leading open workshops in digital art making on programmes such as Procreate and CapCut.

The images in the gallery form an extraordinarily bright, colourful and busy world. There are a diverse array of images displayed on monitors, in lightboxes and on touchscreens. The boys flick through tens of images on the screen bringing up different ones they choose to talk about.

A video plays continuously on a monitor. Footage of Country (ngurra) taken from a drone shows the Ngurin (Harding) river, a substantial body of water, snaking through the Country. The town of Ieramagadu (Roebourne) on Ngarluma country, is on the Ngurin and is crisscrossed by large highways and small tracks & roads. As the image moves away from Ieramagadu into surrounding areas, the picture shows lush green vegetation flanking craggy cliffs surrounding an emerald green waterhole. This view of the Millstream Chichester National Park further inland on Yindjibarndi country is contrasted to flat expanses of spinifex flecked red earth which transforms into rivulet-riven golden sandhills as the drone moves towards the sea (Indian Ocean).

The video is an icebreaker as Kerrie asks, as the video image hovers over Roebourne:

‘Is that shot from Mt Welcome or a drone?’

Isaac: ‘that’s a drone’

Kerrie: ‘Where’s the (municipal) swimming pool?’

Isaac: ‘It should be coming up soon. That’s our little swimming pool over there (pointing towards a spot on the river as it comes closer into view)’

Kerrie: ‘is it cold or warm water?’

Isaac: ‘cold now but it’ll warm up’

Kerrie: ‘Do you fish in there too?’

Isaac: ‘Not allowed to fish in there’

Kerrie: ‘oh, ok, did anyone draw the river?’

Isaac: ‘Yeah, everyone drew the river!’

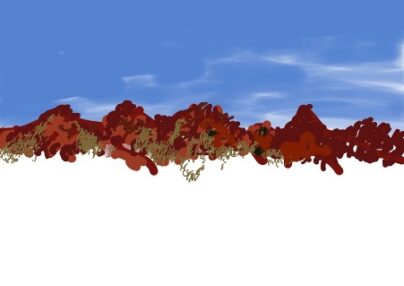

Young artists have created their own interpretations of landscape. The myriad images offer diverse perspectives of the town, the younger artists’ home, and their Country. Two of Fabiarna’s artworks feature the rocky red outcrops of Murujuga (the Burrup Peninsula). Each artwork presents a different perspective on Murujuga, a site that holds thousands of petroglyphs of inestimable cultural value, and that also doubles as a base for extractive (natural gas) industries. Murujuga National Park has recently been submitted for World Heritage listing (see www.murujuga.org.au/)

Fabiarna Togo, Murujuga 1, 2021.

While some images, such as the one above, feature the landscape, other images hint at ways in which the younger artists, themselves, are embedded in the landscape. Again, a diverse range of images is on display expressing identities, culture and attachments.

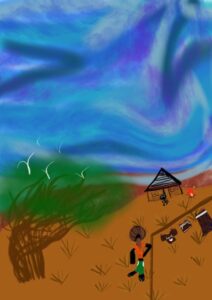

Kimberly Wilson, Windy Afternoon, 2022.

In Kimberly’s striking image the cerulean liquid sky dominates the top two-thirds of the view. In the remaining third at least half is a tree with a verdant green canopy enjoyed by birds. Humans and their structures take up a corner in the bottom right of the image. In the foreground a larger figure in bright green shorts and an orange shirt is standing by a line of clothes hung out to dry in a yard. In the background, a small, spidery figure is placed in front of a house and campfire. In this image of outdoor domesticity, extraordinary detailing marks out shoe straps, pockets, waistbands, and a T-shirt design engraved with the word ‘love’ and a heart symbol.

Kenton directs attention to a different set of images on a touchscreen box. Quite a few feature animals (birds, turtles and snakes) and plants. Some are animated and others are interactive. There is a gif animation of a green turtle swimming (RJ Parker, Turtle, 2021). In another animation, green stems shoot from red/brown earth to be met by rain falling from the sky (Fabiarna Togo, Up, 2022). Kenton is playing with an image of a snake, making it larger and smaller. Patrick Churnside asks Kenton, ‘what’s that?’ Then, after a pause, Patrick says, ‘Warlu, warlu, means snake’.

Amber Stevens, untitled, 2021.

Patrick is a Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi Traditional Owner and senior knowledge custodian. He has been intimately involved in Big hART’s Yijala Yala project, notably performing Tjaabi songs in the touring mainstage production of Hipbone Sticking Out (2013), and has developed a subsequent stand-alone performance, Tjaabi – Flood Country [https://newroebourne.bighart.org/projects/tjaabi-flood-country/] for the legacy, New Roebourne, project. Patrick is a cultural advisor to the New Roebourne project.

He explains his participation thus: ‘my part is being able to help facilitate culture with the young people and helping them to connect intergenerationally …where they may talk about things of culture whether it’s related to some of the portraits they do or whether it’s got to do with plants. For example, some of the types of plants and portraits of plants that they draw. My part is to instil the cultural value of that, talking about skin names, for example, and explaining what that might mean in terms of cultural obligations. So, say this is the sturt desert pea, [he draws up the image, see below] […] when it comes to colours of different plants we connect that to skin group and it then gives the kids that more wider lens learning about what cultural obligations or behaviours they must carry just by drawing a plant.’

Kimberly Wilson, Desert Pea, 2022.

Patrick sees his role as: ‘tell[ing] the story of what gulgawarnigu means and how we connect that not only to everyday learning but, as we say, our living culture of plants and animals.’

He says: ‘I hope that I’ve done it justice […] it makes me proud […] it helps resonate more of the cultural values of some of the portraits of what the young people have been doing.’

Patrick notes that while other organisations pursue ‘avenues of youth outreach’, Big hART’s approach is unique because it provides a space for facilitation of intergenerational cultural learning: ‘the uniqueness of what Big hART does is help young people not only connect to culture, connect to Country, but it gives a sense of having a safe space to do so. Being able to share that on my part as cultural leader and also advisor or ambassador to the company is important.’

After viewing artworks inspired by landscape, plants and animals, the remaining artworks are mainly portraits (widely understood to include images of self or self-created images). Again, these are extremely diverse and innovative in design. There are digitally augmented photo composites, detailed line drawings, abstracts, action figures (kicking a football), fantastical beings (blood sucking vampires/zombies), dot images and spiritual figures.

Issac introduces his little brother, Kenton’s, self-portrait:

Kenton Guiness, All about me, 2022.

He then introduces us to Ngarluma Boi (2022), the image he created, which falls into the latter category.

Isaac Guiness, Ngarluma Boi, 2022.

Sarah asks Isaac: ‘Is that you? Is that a self portrait? Or is it a spirit?’

Isaac responds: ‘it’s a spirit from ngurra [Country], a good spirit’

Sam says: ‘it’s like a happy one’

Kerrie: ‘why did you choose those colours?’

Isaac says, ‘blue is for water, red is for sand, and brown is for country, rocks. When you’re out on Country this spirit protects you, it follows you around.’

Sam: ‘he’s Ngarluma’

That the Country is alive with spirits and where humans comfortably co-exist with other than human creatures, is also clear from Amareisha Woodley’s image:

Amareisha Woodley, Friends and Family, 2021

Amareisha Woodley, Friends and Family, 2021.

This bright land and waterscape, with a mother snake and two young snakes poking their heads out of the river evokes the inter-connection between people, place, plants and the creatures that belong to Country. This Country as kin is a lived experience for these younger artists and frames identity and belonging, as the artwork title makes clear.

Working with Big hART

Kenton says: ‘I love being a part of Big hART – they are a kind and friendly mob. We love to have Big hART in Roebourne. For all us kids, so much fun and laughs. We learn so much like Procreate, CapCut, and much more. It has been so good to make my own work

Isaac says: ‘I started learning with Big hART a long time now. I enjoy everything. It’s so much fun learning different things.

While Isaac primarily enjoys being in the creative flow and building on that:

‘My first thing is creating things with this app called CapCut. My mind gets excited. I get building and building.’

Kenton says: ‘I feel proud, I’m not going to stop. Now maybe one day I can create something different. I’m working on a character to create the future I want and to give life back to what’s been taken.’

The art-making and the exhibition provide an opportunity for younger artists working with digital tools to illustrate how they see and experience their community. For them the plethora and diversity of images depict Roebourne as home and Country (ngurra); it is a beautiful place with some especially famous landscapes, full of friends and family, cultural meaning and connection. The images offer perspective on everyday activities including recreational (football, swimming, fishing, hunting) and cultural learning facilitated by yarning with elders and regular trips on Country. The people and place are richly supportive and sustaining. A sure sense of self emerges from connection to Country and other people (friends, near family, elders).

As Kenton elaborates: ‘The best things at home is hanging out with my friends, we go fishing, play footy in the park, go fishing around Cossack, catch a fish or two, sometimes crabs.

Isaac explains: ‘We go fishing, we go hunting for bush food, mulla: kangaroo; emu; whatever is in season. We try to collect something to eat. I play a lot of sports: footy; basketball; hockey; t-board. At the moment my favourite sport is basketball. I hang out with my friends. We all mainly family. We play sport, ride scooters, share big feed together, hang out with my elders.’

Kenton proudly explains that there are: ‘some famous places in my ngurra – Millstream; Murujuga, the famous Burrup. We go out bush a lot with my dad and mum and family, since I can remember. They teach me about who I am and who my family is and about my ngurra.

We also go out hunting, collecting bush tucker, even visit the ngurra all year around.’ His artwork Bush Boys (2022) reflects that ‘we like to go out bush a lot.’

As well as ‘having fun’ Kenton enjoys ‘yarning with my gurndat, my dad’s nanna, she tells me stories about Country and family. My gurndat is special to my family. She is a powerful woman. I love her very much.’

Isaac also singles out ‘my mother’s grandfather teaching me my Ngarluma connections’.

Kenton says: ‘We, all our family in Roebourne, help each other every day. We don’t have much. I wish we could be rich, but we right, we have each other’.

Isaac concurs: ‘Me and my brothers are blessed to have access to all this knowledge. Also my beautiful gurndat. She teaching me lots about who I am connected to ngurra, families, animals, plants and more’

Sam Walker, Kenton and Isaac Guiness, image credit: National Portrait Gallery

Sam Guinness, the boys’ mum who has accompanied them on this trip, along with elders Patrick Churnside and Michelle Adams, says ‘let me tell you about Roebourne. Roebourne is home (she pauses for emphasis). I’m here […] to tell you the truth about Roebourne. Roebourne has a lot of history in the media and we have a lot of cultural history that keeps us connected to who we are today which is very important.’ While the town is small (with a population just under 1000), Sam says, ‘in the town of Roebourne there are many different language groups that all live in our town: Ngarlarma, Yindjibarndi, Banyjima, Yinawangka […] – I could go on forever. As you can see we all come from different parts of the country but we make it work, we make it work.’

She emphasises her boys’ statements about Roebourne saying, ‘Roebourne is a beautiful place like my sons said. We have some famous spots within our landscape, but […] what the most beautiful thing about it is, is the elders, the connection to it, everything that we have we share, nothing stays to anyone of us’.

Sam notes something the boys haven’t raised, which is the history of negative media coverage of the town: ‘The town of Roebourne itself as we all know is blackened in the media quite a lot, but taking off all those dark clouds it’s a beautiful bright little town you know’.

It is clear that the opportunity to make art and show it publicly in the National Portrait Gallery affords the younger people of Roebourne a chance to create images of their town the way they see/experience their home and their ngurra. The perspectives offered in the artworks are very different to the (negative) outsider perspectives that Sam calls out and counters.

The Role of Big hART and the Digital Lab

Sam: ‘Big hART plays a big role in our community. We are very blessed to have them giving our children many opportunities and showing them what’s out in the big wide world, which is very important. […] I can’t say enough about Big hART. Since Big hART has been in our town we’ve expanded the children’s opportunities.’

Sam notes that; ‘Big hART is the only place in Roebourne where children can go after school – the only place – the digital lab is the only place for our children to attend after school and maybe we would like to get that building a bit bigger because lots of children want to be going in there you know lots of them.’

Sarah: ‘so it’s a safe space?’

Sam: ‘oh yeah, most definitely. It’s culturally equipped because you have our elders – one standing right there now [gesturing to Patrick Churnside]. They are important to us, they are always leading the way. It’s about sharing generational knowledge and custodial laws that are passed down through these kinds of things. Remember we are a living culture so, it’s just brilliant.’

Second generation of younger creatives

Sam notes that her boys are the second generation of younger people to engage with Big hART’s digital art creation in Roebourne:

‘It’s about 13 years since Big hART started. My boys are the second generation that’s come through the ropes.

‘The first generation of children, you want to see them; they are out and proud. They’re still dancing; they’re still in art; they’re still connected, see? Yeah. So my sons are the next generation. Big hART have given them that opportunity to break all those barriers down and just be themselves, you know. The world puts too much pressure on us as it is.’

Finding their Voice so that shame is out the door

Sam continues:

‘I just want to say how important and how significant these kinds of programmes are, as projects giving our children their own voice; their own voice to express themselves through artwork. I noticed the changes in my own boys. They were this shame, you know, (she gestures with her hands far apart). I could go bigger, but you can see they were that much shame. Now that shame is out the door and we now have confidence and self-esteem. All these things that we are all entitled to, they’ve captured now so they’re ready for the next stage.’

Sam indicates that the next stage is critical and may include leading cultural rejuvenation:

‘It’s a small step to a massive change for these children. Everything that we do is in collaboration, we are working together for these children so that everything matters. We’ve got to get it right. They’re not going to stop now. Kenton says that he’s working on a character now about everything that’s been taken from our world. So he’s gonna create this character to give life back.’

Linking digital art making of young people and Tjaabi performances

Patrick says that his stewardship of the Digital Lab and art/culture making is leading him back into Tjaabi performance making.

He states that:

‘coming out of some of these exhibitions and artworks and young people projects, I’m sort of feeling the time is right now to come back to redeveloping and recreating what might be the next phase of Tjaabi shows’.

He reflects on the fact that Tjaabi were toured to active mine sites in the Pilbara:

‘performances were taken to two different parts of country connected though ceremony and song […] Eliwana mine site is based on Pinikura Country west of Gurruma Country […]. While Solomon mine sits partly in eastern Gurruma and Yindjibarndi country […]’

Reflecting on these performances, Patrick states that:

‘It was, you know, a different way of showing community and more so the resource industry sector about what the importance of Tjaabi means in terms of cultural values […] You could say it’s a gentle reminder to say to those that are in the industry that these song stories and this particular form of culture has – where they now see mine pits and mining camps – actively existed. So in that sort of context, I hope it would give them a better understanding of Country and a little bit more appreciation if you will’.

Patrick expanded on this statement stating the performance of Tjaabi was:

‘a way of … reclaiming the Country. It’s putting back what was originally there in a sense – the landscape and the songs and the stories […] regenerating them […] something you hear the elders saying when you dance on the land is we help the land to regenerate and recover […]’.

Acts of ‘Healing’ (Patrick) and ‘giving back life’ (Kenton) – Renewing Ngurra

Patrick characterises his support for digital art making and his own return to Tjaabi performance making (he is also central to upcoming – September – tour of Songs for Freedom) as acts of ‘healing’. His discourse returns to mind Kenton’s desire to go on to create a character that restores or repairs – ‘gives life back to what has been taken’.

The New Roebourne project co-produced by Big hART and Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi communities of Ieramagadu Roebourne offers intergenerational opportunities distributed across multiple intersecting art/media platforms to renew living culture flourishing on Country.

Co-Authors

Patrick Churnside is a Traditional Owner from the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi Language Groups and a cultural leader in his community of Ieramugadu (Roebourne) in the Pilbara WA. To Patrick, arts and culture is about wellbeing, connection and community. It’s a way of life and a sense of identity. Patrick has a strong interest in finding solutions to the issues facing young people who may be considered “at risk”. Patrick is on the board of Big hART. Patrick is a gifted performer and has worked with Big hART leading intercultural workshops in the Pilbara for many years. Patrick’s acting credits include Tjaabi: Flood Country, Songs for Freedom and Hipbone Sticking Out (Big hART). Patrick has toured these productions to Perth, Canberra, Sydney, Darwin and Melbourne. Patrick works to present his culture through the arts. Patrick wishes to be a positive role model and mentor to family members and his community.

Sam Walker is a Ngarluma Munga woman from Yirramugadu. Sam is passionate about community and culture and works hard to protect and preserve its importance. Sam is a Ngarluma journalist and broadcaster who facilitated the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup as a commentator on Meeanjin country in Brisbane where she sat on the symposium panel for Gender Justice. A career highlight for Sam was representing her community on NITV show The Point where she spoke up about her communities strengths while advocating for positive change.

Kenton Guiness is a proud Yindjibarndi Ngarluma boy who was born on Karriayda country and grew up in the town of Yirramugadu. Going out on country teaches Kenton about who he is and his families connection to place. Kenton likes to play footy and basketball on the weekend and in his spare time he likes fishing for Milinja and collecting bush tucker. Kenton’s Nanna Gurndud is an important woman in his life who teaches him about his country and culture. Kenton expresses his personality through art.

Isaac Guiness was born on Karriayda Country but spent most of his days learning and growing up on Ngarluma country. Isaac’s father is Yindjibarndi Ngarda and his mother is Ngarluma Munga. Isaac learns about who he is through his family and enjoys yarning with his elders about the good old days. Isaac loves playing footy, basketball and hockey and likes to ride scooters on his days off. Isaac enjoys learning about new technology and showing the beauty of country through digital art.

Sarah Holcombe is a Senior Research Fellow in the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining at the University of Queensland, Australia. She is a social anthropologist whose applied research finds the chinks and levers where Indigenous locals can assert their rights and interests. She has critically explored the concept of ‘human rights’ in Central Australia, which included a translation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into Pintupi-Luritja (see Remote Freedoms: Politics, Personhood and Human Rights in Aboriginal Central Australia. 2018. Stanford: Stanford University Press). She also researches relations between the mining industry and First Nations communities. Her critical examination of industry benefit packages has found that they tend to ignore community-based cultural aspirations which are the basis of strengths-based approaches to creating sustainable (cultural) livelihoods on extractive frontiers

Kerrie Schaefer is Professor in Community Performance at the University of Exeter in the UK. Before relocating to England in 2007, she worked at the University of Newcastle, NSW. Her research explores international theories and practices of community arts (cultural democracy and cultural rights). In 2013, Kerrie visited Roebourne to follow a two-week creative development by Big hART as part of the Yijala Yala project. She wrote up a case study on Hipbone Sticking Out for her book on community and performance (see Communities, Performance and Practice: Enacting Community. 2022. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan). She argued that Big hART’s Yijala Yala project was building on cultural strengths and making visible to the nation a culturally competent community, revising less positive narratives circulated in the media in the process.

The Digital Lab is home of NEO-Learning an education platform for primary school teachers and students to give access to quality First Nations digital arts content, resources and live virtual experiences. For more information on NEO-Learning visit https://neolearning.com.au/